"Affordability" is a Cause Without an Enemy

It's a wonderfully inclusive theme, but tests a basic rule about narrative

“They have this new word, affordability,” President Trump said last month, referring to the electoral theme that united Democrats from New York City to Virginia, and is sure to frame the next election as well. Of course it’s not a new word, any more than the word “groceries” that the president pronounces as if he’s just learned how people without servants obtain food.

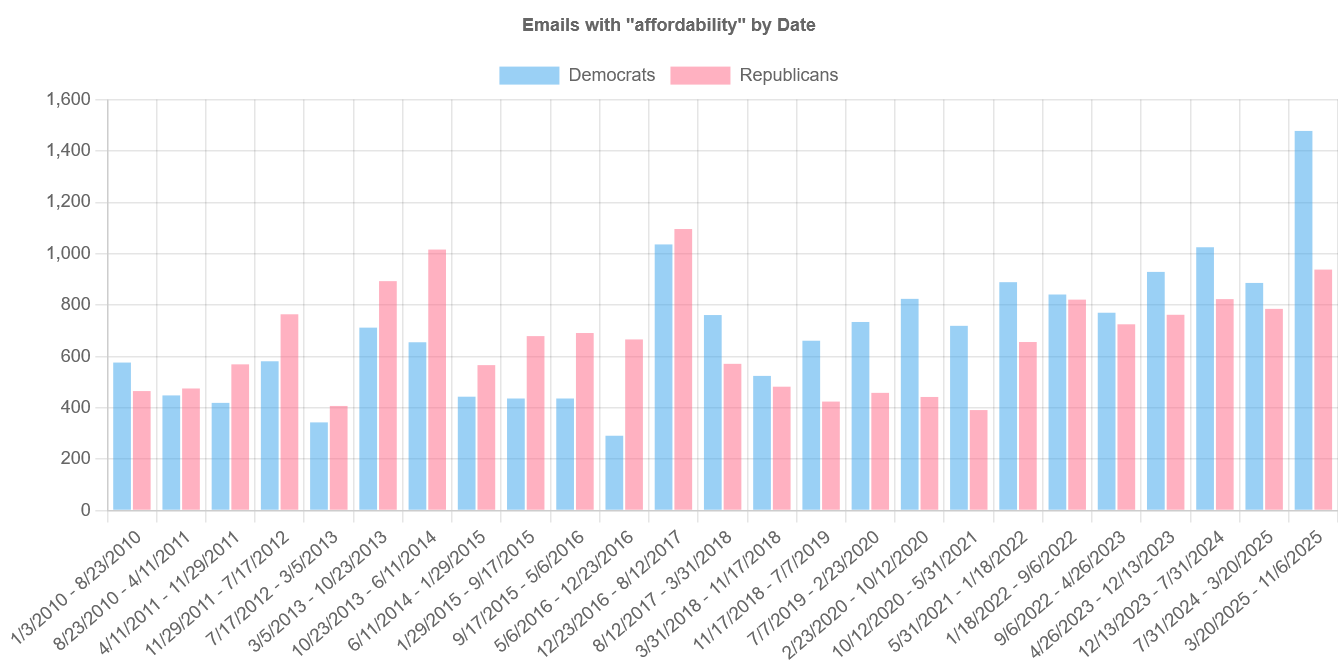

Affordability is a familiar theme in American politics, but it’s often been used with a modifier: Politicians talk about college affordability, or health care costs, more often than the one word on its own, and the use of the word has gained traction in just the last year, as measured by its use in official emails from Democrats in Congress.

On its own, the word creates a capacious political theme. It’s a plain-sense word that won’t wind up on any list of “words to avoid,” such as the one put out by the centrist lobby group Third Way that targets useful but specialized phrases such as “food insecurity.” It goes well beyond “inflation,” which represents only the recent change in prices for a basket of goods and not all our experiences of costs. The word also encompasses costs that are persistently high, as the result of past inflation, although actually bringing down prices across the board—deflation—is usually associated with deep recession. Far better, as Heidi Shierholz of the Economic Policy Institute argued recently, would be policies that raise wages, which is the other dimension of affordability. Median wages rose during the Biden administration, but price inflation negated most of those gains; wage gains with steady prices would have the same effect as lowering prices. As Becky Chao and Mike Konczal of the Economic Security Project say in their excellent recent paper, “The Affordability Framework,” affordability is where “broken incomes” and “broken markets” meet.

Affordability is universal, but also a young adult issue

If “things cost too much” (inflation) and “I don’t make enough” (income) are two dimensions of affordability, there’s a third dimension, which is something like, “I can’t afford what I most need at this stage of life.” The costs of housing (rental or first home purchase), child care, and higher education or training (whether current or financed by debt), and health insurance are not only high, but often pile up at exactly the period in the life cycle, typically, one’s 20s and early 30s, when people’s incomes tend to be lower, they are more likely to be managing student loans and other debts, and they may want to reduce their hours of work if they’re starting a family.

“Affordability” is a powerfully universal theme, but it hits differently for someone with a recent degree (or still completing their schooling), considering having children, aspiring to buy a home, and burdened by debts, compared to someone later in life with a nearly paid-off mortgage from 20 years ago and no need for child care. Although some costs hit later in life, usually people are more settled at that point, their incomes are higher, and they’re more likely to have a buffer of savings.

It’s become commonplace to say that the current 25-34 generation might be the first that will not do better than their parents. That remains to be seen—it’s been said in the past, too. But there’s no doubt that the generation’s current circumstances are particularly difficult, and also that, politically, they are volatile and persuadable.

“Affordability,” then, is both a universalist response, and one that’s targeted to the concerns of a portion of the population that most needs support. It also creates a new language to talk about a “care economy,” particularly child care, paid leave, and flexible work, in a way that speaks to both men and women.

Who is the affordability villain?

But there’s one puzzle about the Democratic and progressive embrace of the theme of affordability. It seems to violate a broadly accepted dogma about political narrative: Stories need a villain. MAGA, of course, is all about villains. Anat Shenker-Osorio, the preeminent consultant on progressive narrative, reminds us that a compelling political argument should be based on “values, vision, and villains.” Messages that describe a problem in the abstract, without naming the bad actor(s) responsible for the problem, don’t resonate or persuade. This insight has become familiar wisdom, and Democrats have sought to move on from Obama’s high-minded language of solving problems together. And many economic narratives lend themselves to naming a villian—greedy Wall Streeters or private equity, health insurance companies, etc., though these stories often oversimplify the real dynamics.

So why doesn’t anyone seem concerned that “affordability” breaks this principle? Who is the affordability villain? Or is it possible that the message is strong, even without naming a bad guy?

One way to square the circle is to argue that affordability is, to borrow Konczal and Chao’s word, more a “framework” than a narrative. Within the loose and inclusive concept, there are a dozen ways to tell the story, and their paper includes many of them, and many of those stories could be structured in a way that clearly identifies the bad actors, or those who profit from making life less affordable. Another possibility is that for the majority of Americans, the villain is right there, occupying our attention all the time, in the form of Donald Trump. He hardly needs to be named, and even if he’s not directly responsible for, say, the high cost of child care, he’s the president and most people now dislike him and distrust him.

But it’s also possible that every story doesn’t really need a villain. Sometimes a language of shared problem-solving, working together rather than placing blame, can be effective, too. Progressives often cite FDR, declaring in Madison Square Garden in 1936 that the wealthy bankers hate him, and “I welcome their hate” as an example of a vigorous, inspiring naming-of-villains. But FDR had many moods, and for every “welcome their hate” moment, there were others where his theme was “bold, persistent experimentation” to bring the economy out of recession, or the sense of shared purpose needed to mobilize for WWII.

Language of shared purpose may seem flabby or inadequate to the challenges of this moment, a leftover from Obama’s naivete. But it also has a rich tradition in American progressivism and, in the form of the “affordability” theme, might still have some relevance to the fights ahead.